The Rural Decline: A Spanish Case Study

This blog briefly illustrates two research papers on rural-urban imbalance in Spain. Two papers investigated in different areas. Palacios states from a historical perspective on how agricultural areas suffer from higher unemployment rates and weaker economic development compared with the rest of Spain. Viñas discusses the internal imbalance of a mountainous province, showing that the gap exists among several indicators like age structure, unemployment rate and income inequality. He also indicates that the geographical factors like travel distance to the urban areas is the main disadvantage for the relatively poorer areas.

Socioeconomic state of Spain

Spain is a developed country. It is a high-income country and an advanced economy, with the world's fourteenth-largest economy by nominal GDP. Spain has one of the longest life expectancies in the world at 83.5 years in 2019 and it ranks particularly high in healthcare quality.

Following the financial crisis of 2007–2008, the Spanish economy plunged into recession, entering a cycle of negative macroeconomic performance, leaving over a quarter of Spain's workforce unemployed by 2012. In aggregate terms, the Spanish GDP contracted by almost 9% during the 2009–2013 period. The economic situation started improving by 2013–2014. By then, the country managed to reverse the record trade deficit which had built up during the boom years. In 2015, the Spanish GDP grew by 3.2, which was the highest among the larger EU economies that year. In just two years (2014–2015), the Spanish economy recovered 85% of the GDP lost during the 2009–2013 recession. This success led some international analysts to refer to Spain's current recovery as "the showcase for structural reform efforts''.

Assessment of urban-rural dependency

Rural unemployment or underemployment in Andalusia and Extremadura (two autonomous communities in Southern Spain) has been an enduring problem. For centuries, agricultural workers have suffered through unemployment, underemployment and poverty as a consequence of the pattern of land ownership and labour organisation.

Palacios, S. P. I. (2007) conducted a survey on the lived experience of rural farmers. They found that the young farm workers are socially excluded, not only because they are currently unemployed but also because they have few prospects. Young casual agricultural workers are excluded from secure employment and lack work experience, as they are usually formally unemployed. They do not have the opportunity to work for more than a few days per year, and then often in only the most unskilled and lowest-paid tasks. Although the government designed a welfare state system, the system is not promoting social integration. Government handouts, initially the Communal Employment benefit and later unemployment benefit, are perceived more as a ‘charity’ than as a ‘right’. For the first time in centuries the families of agricultural workers have a regular income, but the means of obtaining it is a source of shame and humiliation for them. Being unemployed and receiving benefits is seen as disgraceful. Farm workers feel ashamed of receiving welfare assistance.

Table 1: The unbalanced distribution of unemployment (Palacios, S. P. I., 2007)

Key findings

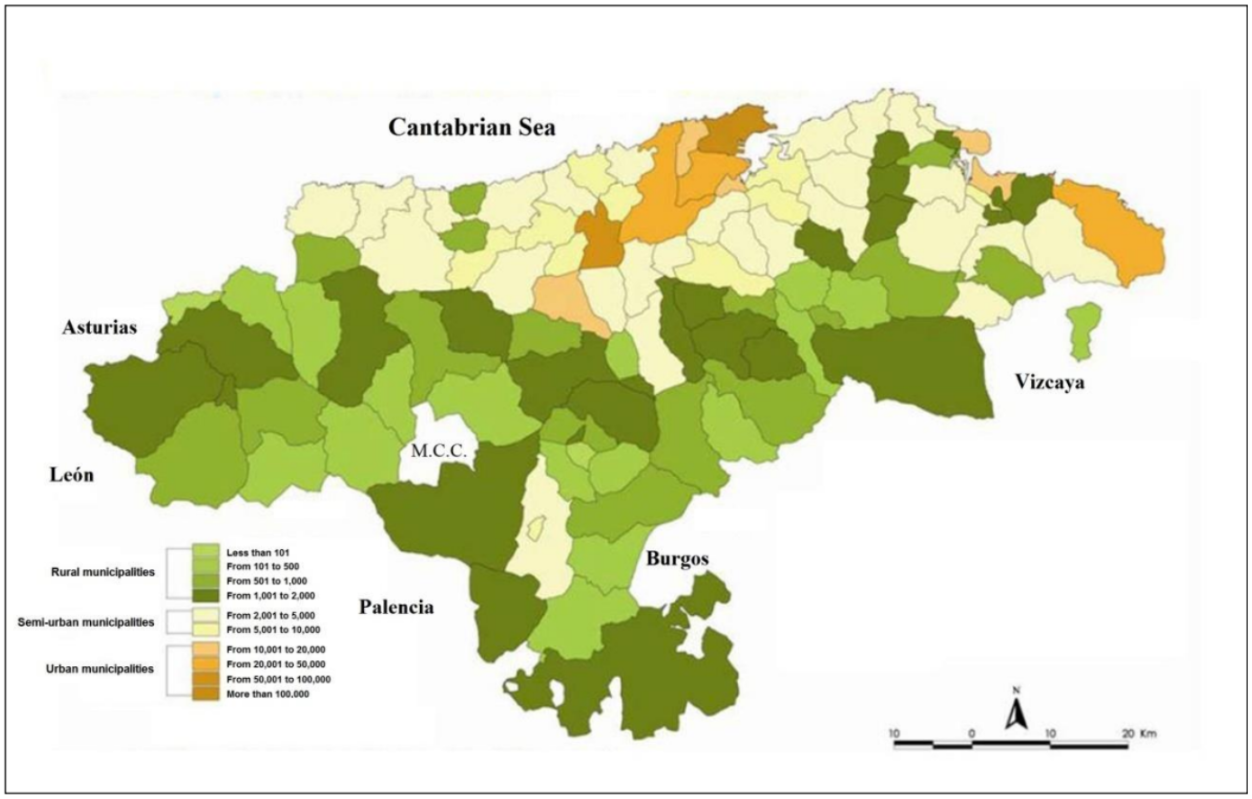

Figure 1: The Autonomous Community of Cantabria in Spain

Viñas, C. D. (2019) uses data in another autonomous community, Cantabrian, to demonstrate the rural decline. Cantabrian is a northern province of Spain with high altitude. The territorial reality constitutes a natural disadvantage since it hinders economic activity and mobility and represents an obstacle to regional development that must be overcome through compensatory measures. Hence, rural mountain areas in Cantabria are at a clear disadvantage because they are less accessible, and it is more difficult to use the land for agricultural production.

Although road transport and communication infrastructures have improved considerably in recent years, marked territorial differences remain in terms of connectivity and accessibility. These differences were measured according to the distance in travel time from the main centre in each municipality to the nearest city with more than 30,000 inhabitants, a population size that ensures the availability of a sufficiently wide range of services. Furthermore, all these urban areas are located close to the north coast. Consequently, the southern half in the region, which is the most mountainous area with the natural barriers to mobility, is precisely the one furthest from these centres.

Figure 2. Distribution of Cantabrian Municipalities

A high number of municipalities have quite rapid access to the nearest city: less than 30 minutes in 28 cases. In contrast to these “fortunate” cases, however, the inhabitants of another 16 rural municipalities have to travel more than 45 minutes to reach a regional or sub-regional service centre, placing them at an evident disadvantage in terms of purchasing goods and using anything beyond basic services.

Depopulation and ageing problem

Figure 3: Cantabrian population dynamics

The greatest spatial contrasts between urban and rural areas occurred during the period of industrial expansion, which was when the largest population losses were recorded. Between 1950 and 1970, the population in Cantabria increased modestly (15.37%); however, 74 out of 102 municipalities witnessed population losses, many of which were very significant. At first, the process of what could rightly be described as depopulation mainly affected mountain areas in the south-western and central sector of Cantabria. Only those municipalities located close to the urban centres experienced significant growth. The accelerated process of depopulation in rural mountain areas continued and became more intense until the end of the 20th century. The result for the second half of the 20th century was bleak. While the regional population grew by 32.16% between 1950 and 2001, 71 municipalities experienced population decline: 27 of them lost over 50% of the population they had in 1950 and 6 of these lost more than 75% of their inhabitants.

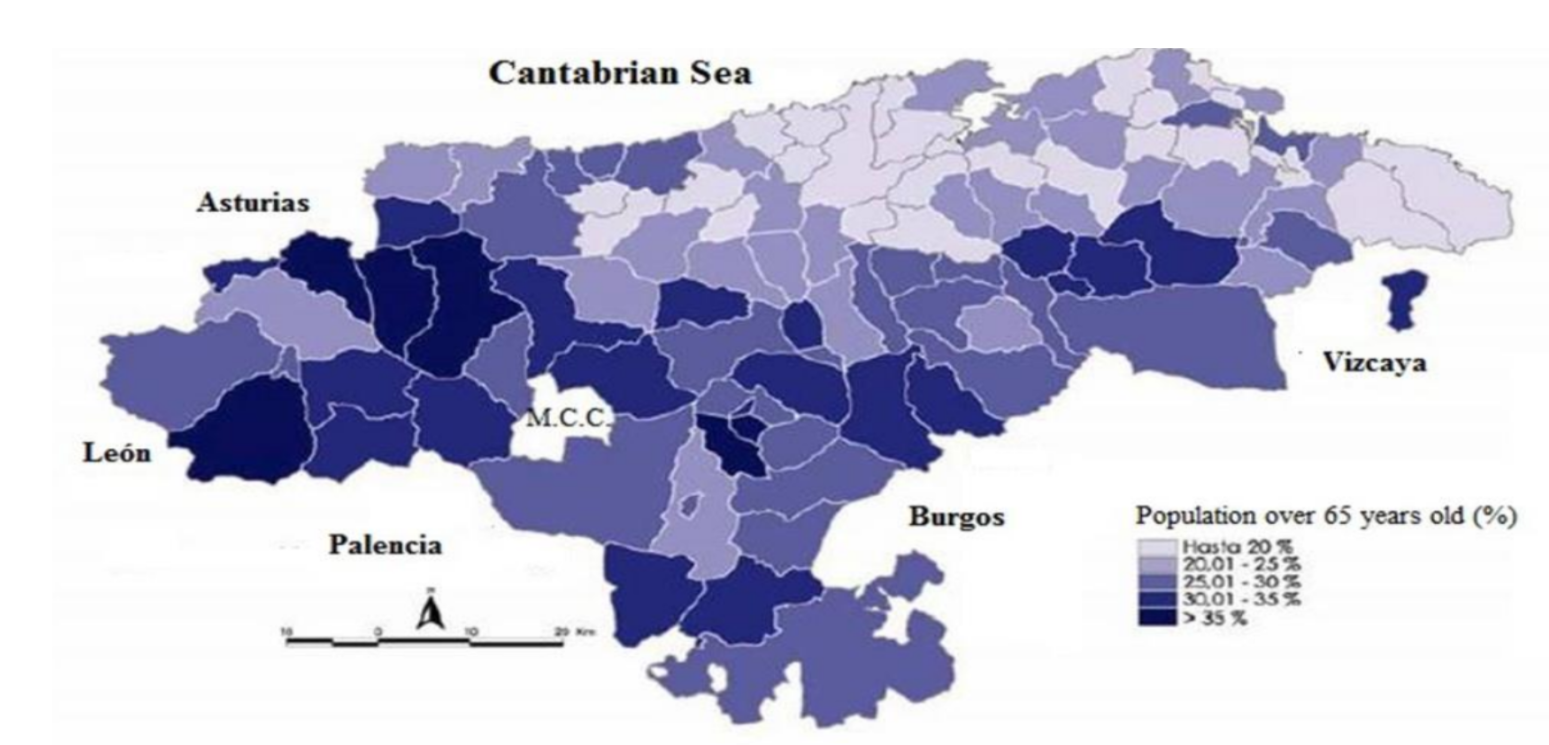

Figure 4: Ageing rates of Cantabrian population (2016)

The areas with the lowest levels of human occupation are also those with the highest rate of ageing, which means that the rural depopulation is mainly caused by an outmigration of young workers. In many rural municipalities, the percentage of people aged over 65 years old exceeds the mean value for rural areas in Cantabria (27.72%). Municipalities in the southern mountain districts, and especially in the western (Liébana and Tudanca) and central (Campoo) quadrants, present the highest rates.

Figure 5: Distribution of per capita gross available income (2015)

Gross disposable income per capita is an indicator that synthesises the imbalances observed in the unequal distribution of the other indicators analysed above. Together, these clearly highlight the disadvantages affecting most rural areas, particularly those with the fewest inhabitants. According to data from the Cantabrian Institute of Statistics, the mean gross disposable income per capita in the region in 2015 was €14,190, but there were marked differences between areas. Once again, a directly proportional relationship can be observed between this indicator and number of inhabitants: the lowest incomes correspond to rural municipalities with fewer inhabitants, whereas the highest correspond to the most populated semi-urban and urban municipalities. From a spatial perspective, the distribution repeats the pattern observed for other indicators: the highest incomes are found in urban areas in the north-eastern half of the region, where the major regional cities and their peri-urban municipalities are located, whereas the lowest incomes are found in small rural municipalities in southern mountain districts.

Cause of the problem

Most of the research coincides in pointing out that the process of population loss in European rural areas is not the result of a specific crisis. It is due to a two-century-long structural situation that has been aggravated by certain episodes. From this perspective, depopulation may be seen as a specific case of a more general phenomenon, which was the rural exodus caused by modern economic growth. The generally accepted causal factors that explain depopulation processes include demographic regression, deagrarianization, poor transportation links, etc.

In relation to the theories describing changes in the economic system, some authors defend the idea of the disintegration of the traditional mountain economies that were based on agricultural activities. It therefore seems that integration in a different economic system and globalisation produces an acceleration of depopulation processes. These changes have stimulated and aggravated territorial polarisation dynamics that have triggered especially intense effects in areas with less capacity to compete. Mountain areas have a less diversified economic base, more difficult accessibility, more orographic and climatic disadvantages for agrarian production, smallholder farms, etc.

These socioeconomic disadvantages clearly explain the current problematic situation of mountain areas in Cantabria and, by extrapolation, of Spain as a whole and even of the European Union. In these cases, depopulation has not occurred as a recent single event but as the result of a lengthy process which will be difficult to reverse. The need to stabilise the current population and also attract new residents demands the implementation of initiatives to improve the provision of basic quality services in the fields of education, health and dependence; to boost physical and online accessibility in all territories by providing appropriate infrastructures; to stimulate economic diversification in order to generate new jobs suited to the needs of the new rural population; and even to implement fiscal actions to ameliorate the situation of particularly disadvantaged rural areas through positive tax discrimination as a territorial investment.